Artificial light at night is a growing human phenomenon that is changing the natural world. As the human population rises, cities expand their borders, bringing artificial light with them into previously dark areas. Alongside an extending range, artificial light is getting brighter as new technologies such as LEDs increase the cost efficiency of powering lights. The natural world has never before experienced artificial light at night at this level and researchers are trying to understand the impacts on wildlife and seek mitigations to protect animals and plants.

Previous studies show that trees growing under streetlights can grow faster, flower earlier, and increase their defences against herbivores – including making their leaves tougher with more toxins. Animals are impacted by artificial light in a number of ways – moths can get trapped in a light beam, some spiders exploit this and build webs by streetlights, while other invertebrates may lose their sense of time and space, staying up past their usual bedtime or getting lost on the way home. So, we know that the impact of artificial light on one part of a food web can affect other parts, and how does this translate into impacts on entire ecosystems?

This project investigates how changes to the feeding behaviour of animals under artificial light at night reshapes the rest of their ecosystem. We’re looking at invertebrates and plants in farm hedgerows and field margins to understand how alterations to these ecosystems might influence pollination and pest control in crops. For a 24-hour period every new moon, when the sky should be at its darkest, we collect flying insects with vane traps and ground dwelling invertebrates with pitfall traps. By identifying the species in these samples we can learn any changes these new floodlights are causing to the food webs. We will look at the DNA inside the guts of predators, such as ground beetles, to see exactly what they’ve been eating. We will measure the amount of different macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein and fat) in the insects to learn how nutrient availability changes under artificial light. At the end of two years of sampling, we can use all this information to draw up ecological networks – complex food webs – and understand how changes to one part of the food web affects another, and how this might impact pollination and pest control.

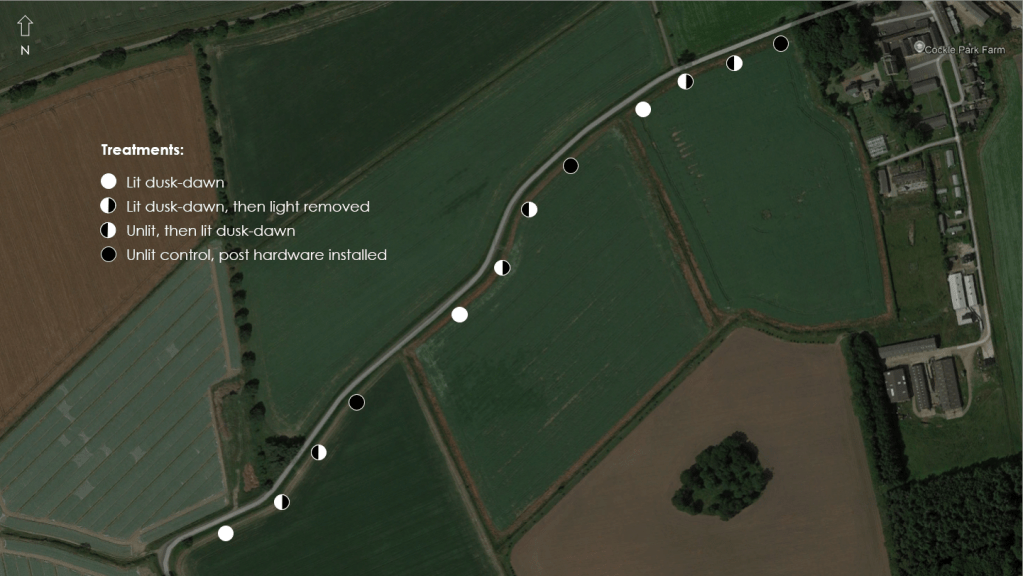

The experiment is designed with four different types of site, and across three fields there are three of each treatment:

- Lit every night from May 2025 to September 2026

- Lit every night from May 2025, then light turned off in summer 2026

- Dark, then light added in Summer 2026

- Dark

These different treatments can show us how ecological networks respond to a new light when it was previously dark, how they recover from a light being switched off, how they respond to light added in summer in the peak of insect activity season, and how the ecological networks are structured without any light added.

If you’d like to learn more about the project, please feel free to reach out to the researcher leading this work, Mia Croft, at m.croft2@newcastle.ac.uk. Here are some links to follow if you would like to read some science about the background and concepts of this project:

- Light pollution as a driver of insect declines

- Insect declines and agroecosystems: does light pollution matter?

- How artificial light at night may rewire ecological networks: concepts and models

- Networking nutrients: How nutrition determines the structure of ecological networks

- Macronutrient Extraction and Determination from invertebrates, a rapid, cheap and streamlined protocol

- Money spider dietary choice in pre- and post-harvest cereal crops using metabarcoding

Mia Croft

Mia is a PhD student funded by the NERC OnePlanet DTP, registered at both Newcastle and Northumbria Universities, and belongs to the Foraging Ecology Research Group. She has degrees in Ecology and Entomology, with previous research looking at invertebrate communities in different sizes of urban woodlands in Bristol, and natural enemies of crop pests in sown flower margins of agricultural fields. She has identified thousands of caterpillars for the University of Oxford’s Wytham Tit Project, monitored the protected large blue butterfly as a Ranger for the National Trust, and designed strategic habitat connectivity projects for the West of England Nature Partnership.