Research themes

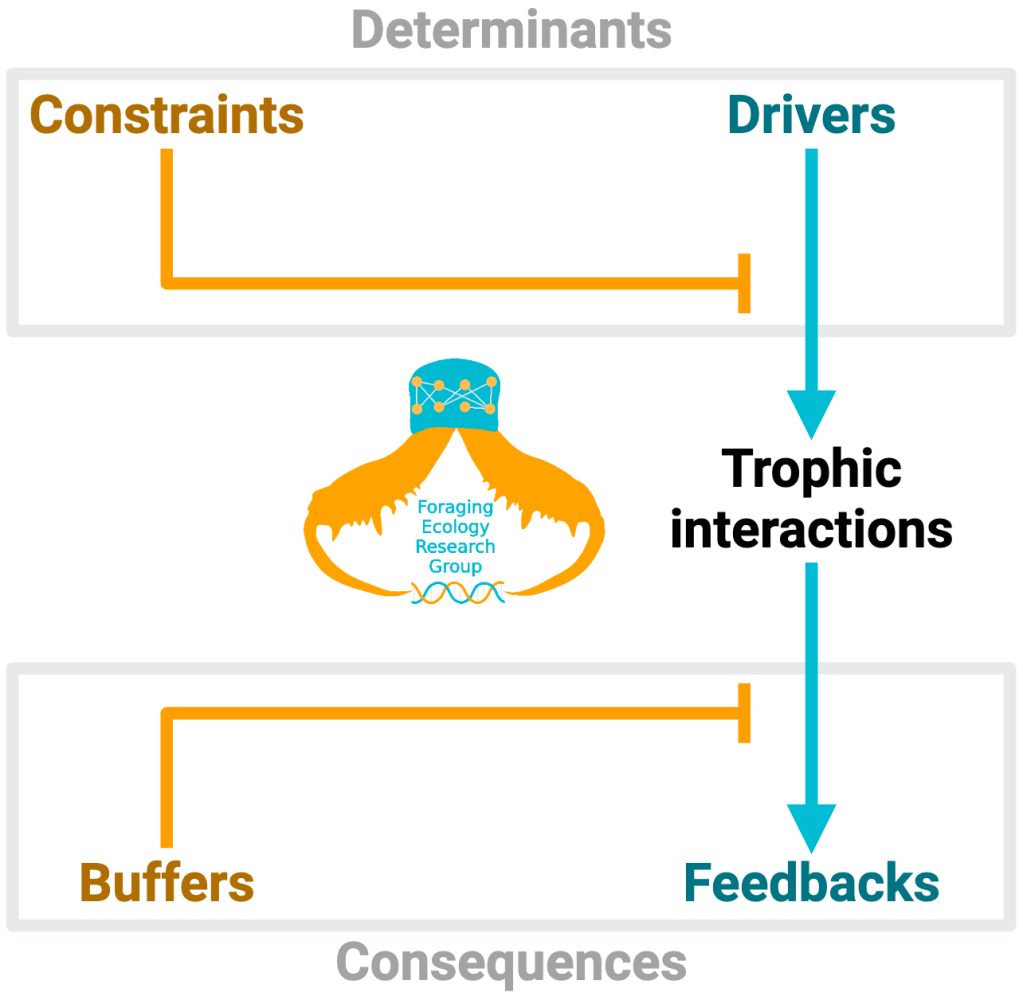

The core theme of our research is foraging ecology, encompassing the drivers and constraints of trophic interactions, the feedback mechanisms of those interactions, and the things that buffer those feedbacks. Our research spans several thematic areas, some primary to most of our research, and others slightly more peripheral, but no less important. Our research addresses real-world challenges in applied contexts, but also fundamental ecological concepts. We combine empirical field experiments, molecular analysis, computational modelling and conceptual insight to advance theory and practice across a range of disciplines.

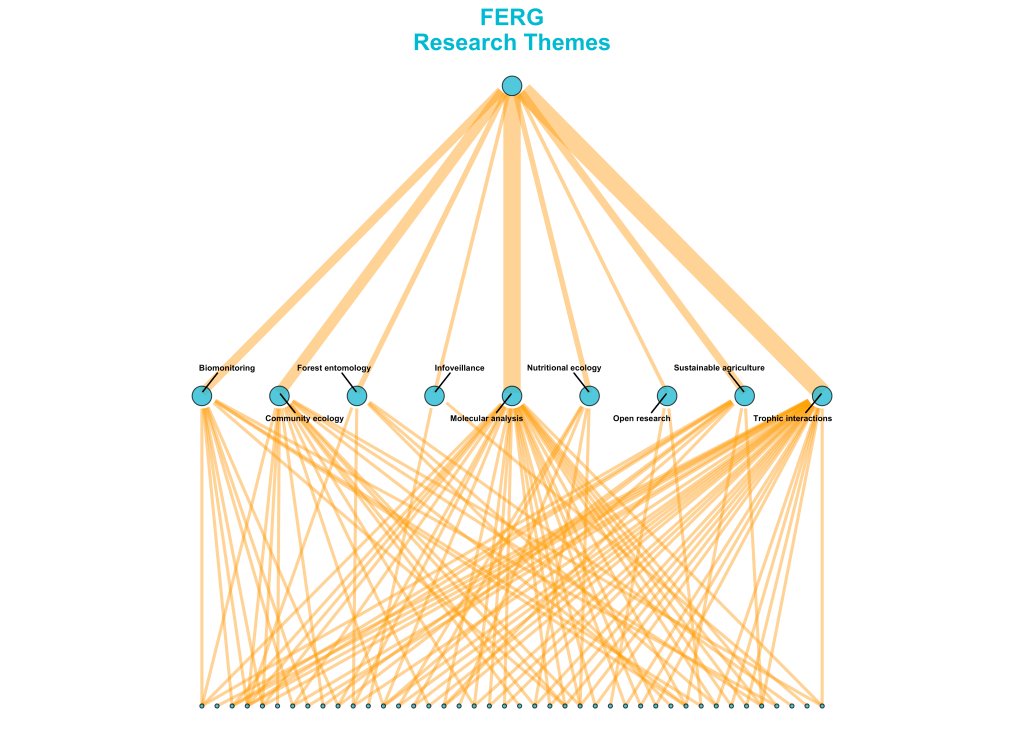

Below, you can see how our published research spans these different themes. Each lower node is a publication, the middle nodes each representing different research themes, and the link weights denoting the number of publications feeding into each. As you will see, FERG’s research is driven by parallel progress across a variety of topics.

Interdisciplinary research

Whilst our research focuses on some key themes and disciplines, a lot of the most exciting research happens at interdisciplinary interfaces!

Both independently and in collaboration with researchers across the globe, we have a strong focus on exploring innovative ideas only possible through the synergy of different research areas.

Core Research Themes

Trophic interactions

Trophic interactions are the fundamental cornerstone of foraging ecology. Our trophic ecological research has mostly concerned invertebrates such as spiders and beetles, but extends to reptiles, mammals, birds, wider invertebrates and beyond. We are particularly interested in how these data can be studied in network contexts, especially when integrating additional context like nutrition.

Beyond simply identifying what an organism eats, we want to identify the mechanisms determining how consumers choose their next meal (prey choice). Alongside critically appraising how we analyse this, we are exploring prey selectivity across contexts including land management and weather. We are similarly interested in interactions such as pollination and predator-plant commensalisms.

Molecular analysis

We are the biggest fans and, simultaneously, the biggest critics of molecular methods. We have critically reviewed how we detect trophic interactions, but also how we process and interpret the data, and integrate them with other data types.

Alongside (and often for) molecular dietary analyses, we’ve designed and tested assays and workflows for everything from nematodes, through aphids and parasitoids, to spider gut contents (including wolf spiders and money spiders and beyond). We love trying new techniques and dabbling in different applications. Most of our molecular research has used Illumina sequencing, but we are increasingly using nanopore sequencing for everything from mitochondrial assembly to dietary analysis and transcriptomics.

Nutritional ecology

As one of the most fundamental currencies of trophic interactions, nutrients are a crucial driving force underpinning foraging ecology. We have developed protocols for the streamlined analysis of macronutrients in invertebrates, including very small ones!

We are particularly interested in how nutrients affect the dynamic foraging ecology of predators, but this interest extends to herbivory, mutualisms and even commensalisms. We are particularly interested in the integration of nutritional data into networks to assess how nutrients structure interactions across whole ecosystems.

Community ecology

Communities are the fundamental ecological units within which foraging takes place, so their diversity, structure and assembly informs all of our core research. We use a variety (and sometimes combination) of traditional and molecular methods to identify species assemblages, both to inform our foraging ecology research but also to characterise and compare communities more generally.

We have compared invertebrate communities to identify the arthropods cohabiting with species of conservation concern, to determine how predators choose their prey, to highlight the importance of habitat heterogeneity, and to assess how species assemblages vary across spatial gradients.

Peripheral Research Themes

Sustainable agriculture

Sustainable agriculture, particularly conservation biocontrol, forms the basis of much of our research. Studying agricultural systems not only allows us to address real-world problems directly, but also provides an often simplified system in which we can investigate some fundamental ecology.

We are particularly interested in exploring how environmental change (e.g., climate change), management decisions (e.g., harvest and crop cycling) and biodiversity affect the interaction between foraging ecology and ecosystem services. This research also intersects with our interest in biomonitoring.

Biomonitoring

Biodiversity is crucial for the functioning of every ecosystem on Earth. Monitoring biodiversity naturally coincides with much of our research. Using cutting-edge molecular tools, we are able to rapidly monitor everything from individual taxa to whole communities, and even networks.

We are driven to advance the application of molecular methods to biomonitoring, particularly to create increasingly representative, realistic and informative data on individual organisms, communities and their interactions.

Forest entomology

Forests are invaluable bastions of biodiversity, and vital productive systems for humans. We have assessed the factors underpinning the presence of species of conservation concern in forests, but also the role of habitat heterogeneity in supporting diverse communities across forests.

We are particularly interested in patchy habitats across forests, such as deadwood and tree hollows, and we are keen to extend our foraging ecology research to forest systems.

Ecological infoveillance

Interactions concerning nature transcend organisms eating one another in ecological systems. Humans increasingly interact with nature through the internet and this vast source of data can help identify how the relationship between people and nature changes over space and time.

Following collaborative research on infoveillance in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we now use these techniques to explore societal perceptions of and interactions with nature to prioritise conservation efforts and assess the influence of nature on society.